The Rear End Of History

Ideas don't matter and boring is good

“for the victory of liberalism has occurred primarily in the realm of ideas or consciousness and is as yet incomplete in the real or material world”

“And I will give unto thee the keys of the kingdom of heaven: and whatsoever thou shalt bind on earth shall be bound in heaven: and whatsoever thou shalt loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven.”

Santiago Ramos wants people to argue with him. Who am I to deny a man his wishes? So here is my belated Christmas gift to him.

Ramos begins with Fukuyama and his “End of History”. This is articulated twice - first in a 1989 article called The End of History? and then in 1992 book The End of History and the Last Man. I haven’t read the book (and you can’t make me) but I have read the article.

Fukuyama makes a number of claims about the world - esp. claims about the ascendance of liberal democracy and free markets. It is easy to mock his 1989 claims about the world from the position of 2025 knowledge (just as I look forward to mocking everyone’s predictions for 2025 this time next year). He downplays the forces of religion and nationalism in ways that seem naive now. But he also downplays the speed at which the Soviet Union will collapse.

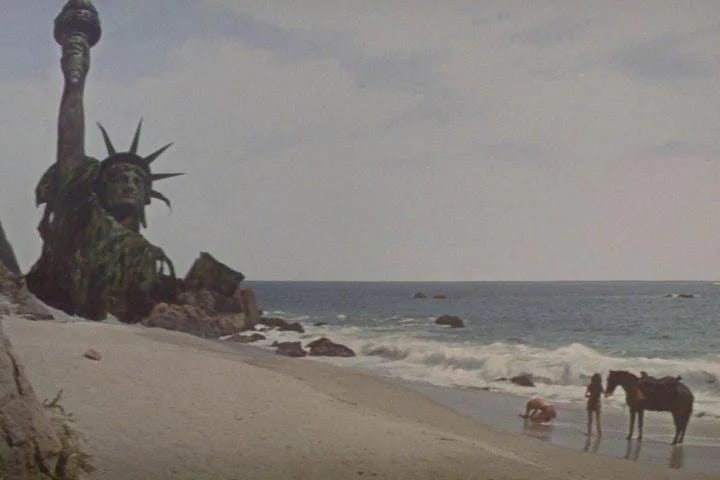

“The end of history will be a very sad time. The struggle for recognition, the willingness to risk one's life for a purely abstract goal, the worldwide ideological struggle that called forth daring, courage, imagination, and idealism, will be replaced by economic calculation, the endless solving of technical problems, environmental concerns, and the satisfaction of sophisticated consumer demands. In the post historical period there will be neither art nor philosophy, just the perpetual care taking of the museum of human history. I can feel in myself, and see in others around me, a powerful nostalgia for the time when history existed.”

As Kylie Minogue did not say: “You should be so lucky to live in such a sad time!” History clearly has not ended. Nor is it likely to end until humanity ends.

Humans gonna History.

But there’s nothing new in that claim. What I do want to argue is that Francis Fukuyama, Santiago Ramos, Damir Marusic, and Lea Ypi do all share a view of the world that, if it is not wrong, does perhaps misassess the world.

Early on, Fukuyama talks about Hegel. And the reason he talks about this German philosopher is that he wants to make a claim for the importance of ideas and ideological analyses of world as opposed to material analyses. I agree with Fukuyama that the relationships between ideas and material conditions and institutions and behaviours are complex and recursive and dialectical. But saying all that, I think ideas are less important than Fukuyama gives them credit for.

The occupational hazard of the academic, the journalist, the intellectual historian is to overvalue words and ideas. Words and ideas are, after all, what this group of people spend most of their time working with. Perhaps if you asked a civil engineer to relate human history to you then they would do so through a narrative that privileges the importance of bridges. Which is fine, bridges are important. But there is more to the world than bridges.

The Soviet Union did more than simply enforce Communist dicta. It also sought to systematically destroy all civil institutions that it could not directly control. So when it collapsed there was little left. The former comrades of the Soviet Union were left with in a world that was both Hobbesian and Thatcherite and therefore terrifying: “There is no such thing as society. There are individual men and women, and there are families.”

If you want to understand the immediate post-Soviet world, look at Crypto. The Crypto economy explicitly rejects institutions that might seek to control and order it. Hence the profusion of blatant fraud and, if you are lucky, less blatant fraud. Likewise if you want understand what a Crypto-first world would be like, talk to the survivors of of Russia in the 90s. Relatives would take out hits on each for their flats or their life insurance. If this was visited upon us, it would be grist to the true crime podcast mill but hell on wheels for the rest of us.

The pain felt in the former Warsaw Pact is as much about failed institutions as it is about failed ideas. Freedom includes the freedom not to be screwed over.

Anyway, on to the two questions that Marusic and Ramos are concerned with:

“Can life be fulfilling if you don’t believe in some bigger narrative of redemption?”

“How do you organize and govern a bunch of people who believe in nothing?”

The answer to the first question is clearly “yes”. People do that all the time. Some people live their lives around ideas. But many more people live their lives around families and work and food and sport and making stuff. They are not the weirdos. If you prod them, then they might make reference to god or something. But they are mostly just getting on with the humaning. It’s those of us with Substacks who are the weirdos.

And I suspect that this has mostly been the case through history. Until mass literacy, the only people we heard from were the Substack writers of their day - e.g. Hegel. So our data is somewhat biased in favour of idea-spouting weirdos.

In answer to the second question, I think that the vast majority of people don’t believe in nothing. Now they probably don’t believe in a rigorously defined ideology or religion - because rigorously defining ideologies or religions is time-consuming and there are better things to do - cleaning up after your kids, cooking the dinner, playing some guitar really badly, listening to your mate going on and on about his footie team until you can’t stand it any more are just four completely random and fictional examples.

But people do believe in something. The challenge of liberal government is to allow these people who believe in many somethings to coexist and to coprosper. And when liberal states fail to do this then people will go elsewhere - to fascism, to communism, to nationalism, to religion, and even, in extreme cases, to anarchy.

“Liberalism provides a modicum of freedom, but millions of people now wonder what freedom is for, what meaning it should serve, and whether society can be structured in a way that better reflects this meaning, whatever it might be”

I don’t think freedom should serve meaning (singular). It might serve meanings (plural). For society to reflect only one meaning requires that many other meanings must be snuffed out or hidden. A modicum of freedom is better than no freedom at all. And our goal should be, perhaps, to embiggen that modicum.

1989 was just 45 years after World War II but Fukuyama was in his late 30 years. He had no direct experience of war. It is easy to have nostalgia for a horror that you never experienced. “May you live in interesting times” is a curse and unfortunately people forget what interesting times feel like. And for those who are asking “How do we make our times more interesting?”, that feels like the wrong lesson to learn from the curse.

Liberalism has always been a failure, just as all political systems are ultimately failures. It is not the final solution* to a problem but the means to live through a predicament. It is contingent. And a little fragile. For history to end would not actually be sad but it is sadly impossible. Humans gonna History.

Are there better ideas out there than liberal democracy? Communism, fascism, nationalism, religion are all deeply unappealing to me. But it would foolish, nay, it would be ahistorical to assume that human beings are incapable of coming up with other ways of organizing themselves.

Some humans will continue to have ideas. Obviously all of these ideas will be wrong. But who knows, some of these ideas might be useful. Even on Substack.

Do I still have to buy tickets for $32.50?

*Fukuyama probably made a good choice in not calling his article “Liberalism - The Final Solution”.

As my dissertation advisor offered, the word “end” means more terminus. It can also mean goal. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YM6p-15fjBg