Tempo – Part 3: Time Travel Agents

The hardcore junglistic techno tracks of the early 90s were made by UK B-Boys (even the name suggests the stutter of a scratched record) who had kept their beloved turntables and breakbeats but artificially sped them up to match the artificially raised metabolisms of their audiences. Resistors in the turntables were doctored to go from +8 to +20. Crude samplers with goldfish memory spans would allow you to speed up your samples. Initially this meant that the pitch of the sample went up with its speed. Everyone sounded like mice on helium.

Then techniques like timestretching and pitchshifting came into play. Timestretching means that you could alter the speed of a sample while keeping the pitch constant. Pitchshifting means the reverse – you can change the pitch while staying at the same tempo. There were particular breakbeat samples that the junglists favoured – a common rhythmic vocabulary or reservoir. The most famous was the “Amen” break – snatched from a 1969 B-side by one-hit soul wonders The Winstons. While pop producers used techniques like pitchshifting to remove mistakes from production recordings (to make them unnaturally natural), the junglists used them as estrangement engines. Meanwhile the basslines that made up these tracks often went at half the speed of the frenetic drums. These basslines were sourced from Jamaican reggae or wholly artificial creations made in the lab-studios of these producers. This gives the dancer a choice – either go nuts to the drums or skank along with the bass. Many tempos all at once.

One such junglist was Clifford Joseph Price (aka Goldie) who released a 1992 track called “Terminator” under the name Rufige Kru. The track starts peacefully enough with some floaty synth work. Then the breaks come in like a swarm of locusts. As if that isn’t enough, at the mid-point Goldie throws in some Belgium Hoover stabs. Then things start getting weird. The drums sound like they are speeding up and slowing down while staying in time. Trompe d'oreille. It would appear that Goldie has been f***ing with the space-time continuum. Then there’s a morse code riff. Terminator is a track that is less terrifying than terrified that dancers will find it boring. It has to morph every few seconds to hold their fickle attention.

What I haven’t mentioned so far are the vocal samples. As the name of the track implies, these come from the 1983 Arnold Schwarzenegger movie. “The Terminator is out there” “You’re talking about things I haven’t done yet”. The film is about technology warping the fabric of time starring a man who had used technology to unnaturally reconfigure his body playing a machine made to look like a man. I have no idea why it was chosen for this this track. No. I got nothing.

A jungle track presents you with all kinds of time. Philosopher and maître-des-calembours Michel Serres notes that French uses the same word (“temps”) for “weather” and for “time”. For Serres, time is not linear, it is chaotic. It stops and starts, folds back in on itself, is sometimes becalmed and then cyclonic. Or perhaps both at once. Time is complex and chaotic and fractal. To my knowledge, rumours that Michel Serres DJed at Speed in 1995 are completely unfounded.

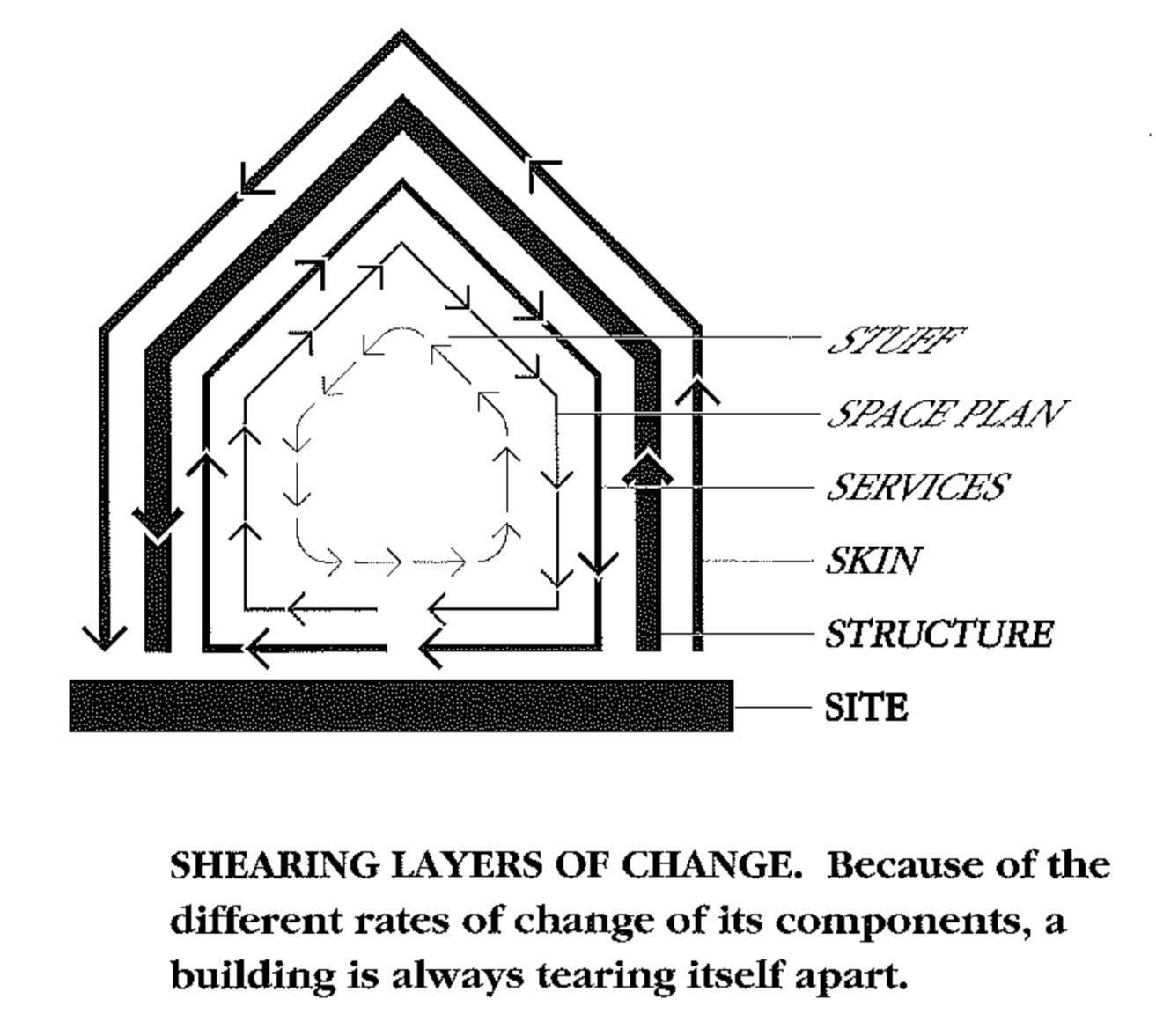

While Goldie was from the Midlands, Jungle’s prime territory was further south in London. You may recall architect Frank Duffy from the previous cut. The “Big Bang” of Financial Deregulation in the City of London (with perhaps Brexit as its cosmic microwave background) and the mass production of the personal computer led to much work for Duffy and his firm, DEGW. A series of research projects called ORBIT (Office Research: Buildings and Information Technology) and building designs articulated a concept that became known as “Shearing Layers”. A building could be conceived as consisting of four layers that changed at different rates:

Shell – the traditional structure of the building that might last for 30-50 years.

Services – cabling, plumbing, aircon that needs replacing every 15 years.

Scenery – layout of partitions and dropped ceiling that last 5 years.

Set – the layout of furniture that might change every few months, weeks, or even more frequently.

The different rates of change of these different layers mean that building design should separate (shear) them out to reduce costly rectification work.

As we discussed previously, Duffy was not a hippy. But his work was picked up by someone who is perhaps the biggest hippy in the world. Like Duffy, Stewart Brand was in San Francisco in the 60s. Unlike Duffy, he stayed there. Initially Brand was famous for the Whole Earth Catalogue – a countercultural magazine and product catalogue that featured on its cover a picture of the earth from space (“the whole earth”). This juxtaposition of the prosaic and the cosmic is typical of Brand. But for Brand, the world is not enough (which is also the name of the movie where Goldie played yet another Bond villain with metal teeth).

Brand was also involved with the technology and business networks that formed in Northern California around Silicon Valley. In 1994, Brand published “How Buildings Learn” – a richly illustrated book on architecture and communities . He drew heavily on Duffy – expanding shearing layers to:

Site (geographical location)

Structure (foundation and load-bearing elements)

Skin (exterior surfaces)

Services (wiring, plumbing, etc)

Space plan (interior layout)

Stuff (chairs, desks, phones, etc)

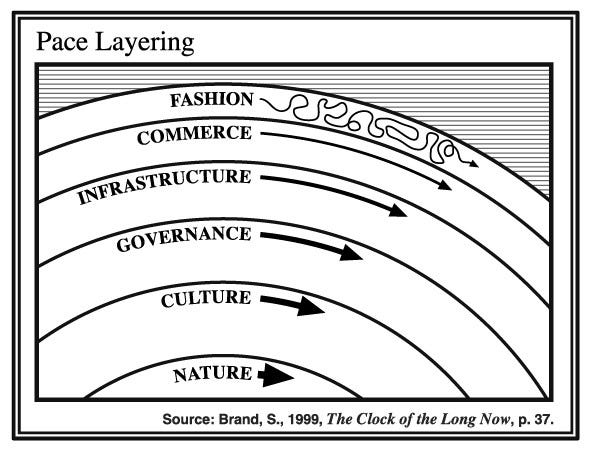

As you might expect from a man who saw the whole earth, he couldn’t stop there. In 1999, he published “The Clock of the Long Now: Time and Responsibility” where time and space are related through the following layers from fastest to slowest:

Fashion

Commerce

Infrastructure

Governance

Culture

Nature

To make a fetish of commercial thinking is to live life at only one speed and to risk tearing the whole system apart. Brand’s response to this is both predictable and insane. In the 1960s, he campaigned for NASA to make public the image of “whole earth” taken from space. Brand and others believed that seeing these images would fundamentally change the mindset and thus the behaviour of human beings – make us more aware of our own fragile inter-reliance. For the last 20 years, Brand and his coterie (incl. Mitch Kapor, Esther Dyson, and Brian Eno) have been seeking to build “a monument scale, multi-millennial, all mechanical clock as an icon to long-term thinking” – The Clock of the Long Now.

While I respect Brand’s organisational abilities and his cosmic imagination, this does seem like a colossal waste of time. The children of the 60s were fond of the power of symbols. And, yes, symbols do have power. But so do economic choices. A prototype clock is being funded by Jeff Bezos – so indirectly the clock is powered by workers in Amazon warehouses – timed to the millisecond by machines that are not of the long now. Just as the whole earth image ensured that we dealt early with catastrophic climate change and prevented wars, so the long now clock will prevent us form falling prey to short term thinking. Or something.

We often forget that we human beings live in many times at once. We are living seconds, minutes, hours, years, decades all at the same time. We may chose to shift our focus from one frame of reference to another but that does not stop the force of life being lived. And we do not need a machine from the future to come back to destroy us – we can do that all by ourselves.

Hi Matt - came across your posts through the KM4Dev group. It is reminding me a lot of Venkatesh Rao's book Tempo: Timing, Tactics and Strategy in Narrative‑driven Decision-making. I'm only partway through it, but all seems relatively resonant.

It's also making me think a lot about an idea for anatomic time, Bergson's ideas of time as subjective durations, and pace layering.