Performance Management

It's time to light the lights

In organizations, perception trumps reality. Reality is hard to get to unless you are right there, in the room or in the field or in the hold of the bomber. So perception is all important. Typically a manager will try to do this through reports that get sent upwards. The world is reduced to a spreadsheet or maybe a PowerBI dashboard if you are feeling frisky. It has always struck me that you don’t drive a car by looking at the dashboard - indeed the less you look at the dashboard the better. But extensive reporting can certainly give the the warm delusion of control.

I don’t want to completely dismiss reporting. Data can be very useful for helping to quantify and validate your experiences. But far too often, it is mistaken for the world in and of itself. And it’s not. By its very nature, it simplifies the world and leaves out information not seen as important.

And we tend to report on data that is easy to collect rather than the data that actually matters. It’s like measuring the health of a marriage based on hours spent in the same room together.

And even then, we are often dependent on human beings to input data. Humans who are busy and distracted and sometimes lazy. One place I worked had a huge number of sales assigned to a particular location. Not because the sales were happening there but because it was the first option on the drop down menu.

Reports become a kind of performance. Like a peacock fanning his feathers at the object of his desire, managers will fan their spreadsheets and dashboards to impress their superiors.

As you move up the hierarchy further from the coal-face where work actually gets done, performance becomes more and more important. You are selling confidence to your peers and bosses. You are calm and in control. You are Living The Values. A Team Player.

And a lot of the time, that is a performance. We are often lost and confused and anxious. We cannot show that. We cannot show weakness. So we must perform strength. If we perform weakness then it must be in the acceptable form of “authenticity”.

We dress in the accepted costume of the executive in the culture to which we belong - expensive suits for investment bankers and management consultants (Fridays; chinos or expensive jeans), expensive hoodies and fleeces for start-up execs, expensive trainers and elaborate wardrobes for advertising creatives. By the costumes we wear and the props we use, we perform our membership of our tribe and hence earn our right to belong.

Our offices and working spaces feel like sets. The cubicles and kitchens and meeting rooms with names like “Paris” and “Tokyo”. The offices often feel interchangeable. Even the ones owned by creative agencies with motorbikes hanging from the ceiling. The sets are there to ensure the actors know what production they are performing in. That is one of the risks of working from home. Without the stage to guide you, you might mix up your lines.

We are, ultimately, acting a role. And like a Greek chorus member, we have donned what John Keegan called The Mask of Command.

Like any performance, this requires effort and work. And it is rarely flawless. The mask sometimes slips. We break character. We reveal the self that we want to keep hidden.

The willingness to put in the labour of continuous performance is the key differentiator of the successful executive. For most people, this all just seems like a massive ballache. But for the driven, who aspire to the highest levels of the royal court C-Suite, it is all necessary.

We sometimes wonder why, despite all the busyness and stress, our organizations do not actually do very much. Well, with all that energy and focus going into performance, how could they? No one expects theatres to ship widgets.

To be fair, I don’t think we can escape the performative nature of human existence. As the greatest dramatist in the English language (I am of course referring to Piers Morgan) wrote:

“All the world’s a stage, And all the men and women merely players; They have their exits and their entrances”

However, as both fellow performers and audience, we might treat our fellow performers will more grace and understanding. We might invite them to perform in new ways, to seek new scripts, new sets, new costumes, new lines. We might, even, occasionally, relieve them of the burdens of performance.

Obviously a lot of what is written here is inspired by Erving Goffman.

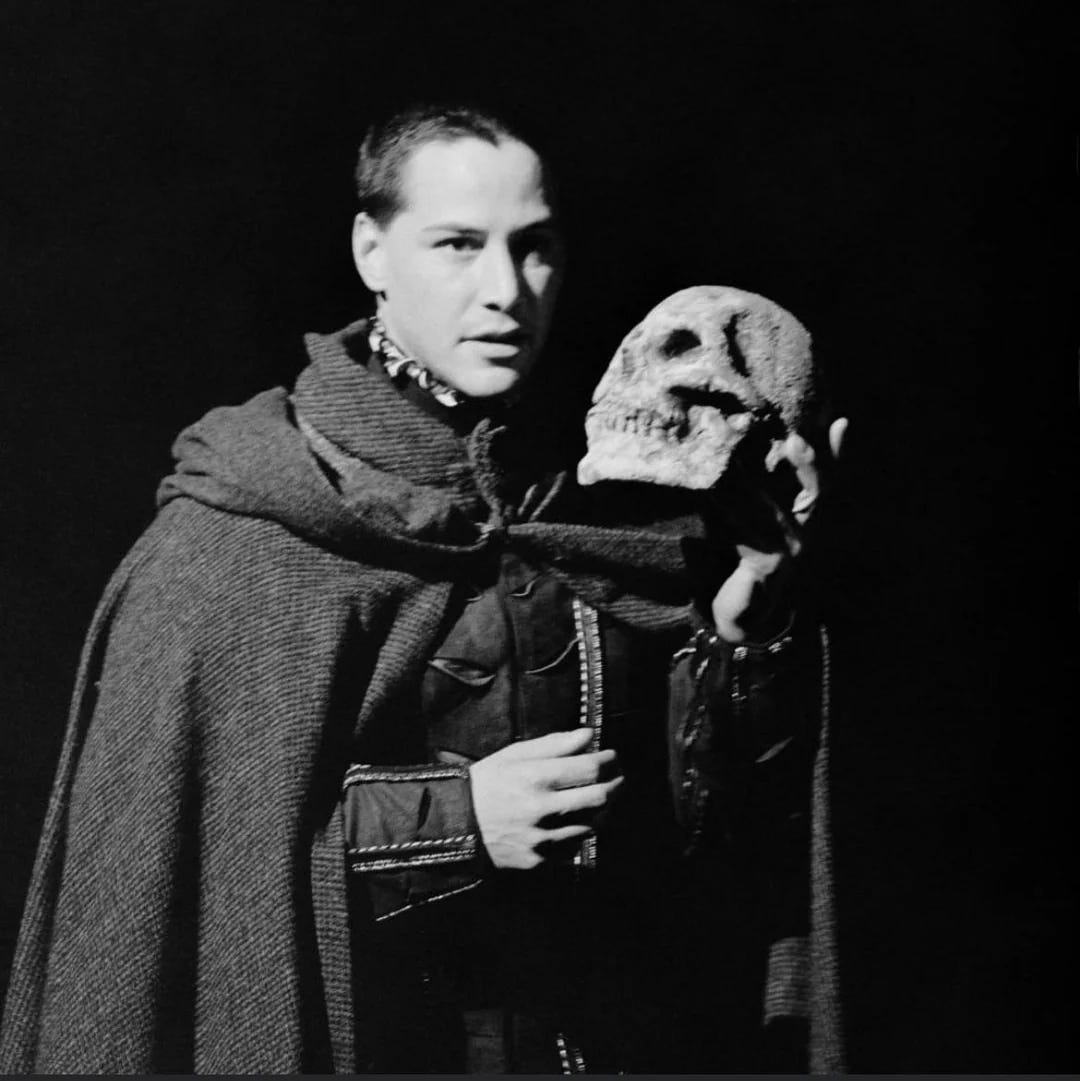

Laurence Oliver performing Macbeth, Bristol Old Vic, 1957

2 comments:

1) You drive 1 car and therefore can afford to look at the road instead of the dashboard. What happens if you need to drive 100 cars on different roads, all at the same time?

2) I like Piers Morgan's writing 😂

Laurence Olivier, shit, I thought it was Keanu Reeves...the keanuification of the internet 🤷♂️

Great article and one I'll be applying to my own professional life situation, which interestingly, takes place at a coal mine.