…in organizing strategy to feed the budgeting process, recognize that the importance of budgeting — revenue budgeting in particular — is overrated

Carlsberg Roger Martin is probably the best beer writer on strategy in the world. In particular, his Medium site just keeps throwing down excellent, no BS posts on what strategy is and isn’t. Martin has been clear in his view that many business executives confuse two things with strategy: wooly vision and values statements on the one hand, and detailed planning and budgeting on the other. In this post, he talks about strategy, budgeting, and time.

I want to riff off this and reflect on how budgeting is both more and less important than many organizations treat it.

The first point is that a strategy cannot be implemented without resources (even if it is just one person’s time). At its best, a budget forces you to get real about your strategy. And conversely, an outsider should be able to look at your budget and understand your strategic choices. Where are you playing and how will you win there? If your strategy truly reflects your values then Joe Biden’s favorite quote follows: “Don't tell me what you value, show me your budget, and I'll tell you what you value.”

However many organizations have not explicitly thought through the strategic choices that they need to make. Their version of strategy consists of statements about customer-centricity, digital-first, being the best, high performance etc. Now none of these are bad things. But that’s the problem. They are so blandly positive as to be meaningless. Has the organization chosen to focus on customer intimacy rather than product leadership or operational excellence (to use the Treacy and Wiersema framework)? “No, no”, come the answer, “we are obviously all three of those at once”. Which is equivalent to saying that you can be a champion weightlifter and jockey at the same time. Pity the poor horse that many executive strategists ride on.

But lets say that you do make strategic choices about where you play and how you win, what does this mean for your budget? For a start, it means abandoning the resourcing s***-fight that is most budgeting exercises. A departmental head overbids for the resources they need and waits for Finance to beat them back down. Instead a saner approach (that will therefore likely never happen) is to cost out what the agreed strategy requires for execution.

We should also abandon the annual budgeting cycle as default. This suggestion fills people with horror because who wants to go through the agony of budgeting more than once a year? Well, part of the problem with annual budgeting is that there is no flexibility in it. You need more? Well, tough, you should have asked for it 10 months ago. So you ask for as much as you can at the start of the cycle. Instead the budgeting cycle should follow the strategy cycle and be dictated by context. Many businesses absolutely run on an annual cycle (e.g. tourism flows are annual, retail has defined spikes). However much business activity does not. “But what about our financial reporting?” I hear you say. So you are going to let government regulations drive your business behaviour? Sure. Perhaps if the market changes then your budget needs to change? This means that budgets may run for more or less than a year.

This should drive strategy and finance teams to see a budget not only as a resource plan but also as:

A series of linked hypotheses

A series of linked bets

Your budget hypotheses around revenue and cost should be constantly reviewed and tested. Accurate budget variances are measures of how good your hypotheses are. And your hypotheses don’t have to start off awesome - they just have to get better with time. If your hypotheses prove to be incorrect then your first move should be change them. Also the validity of hypotheses is not static, therefore you need to continually review them. What may have been true last year may not be true this year.

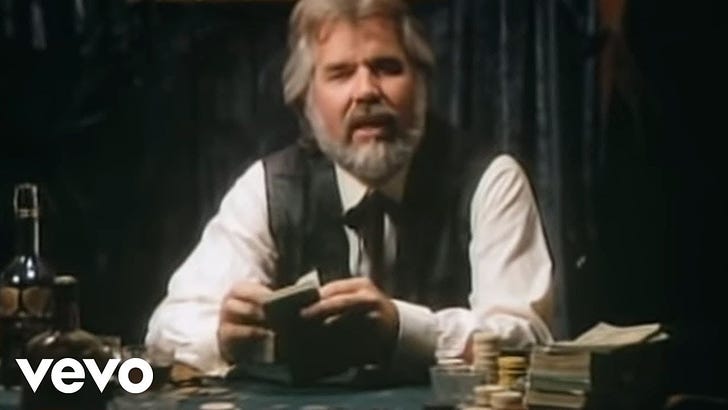

Your budget bets require some measure of risk. Rigorously quantifying this risk may be unhelpful if these are risks that resist quantification (e.g. the success of a disruptive product in a new market). Quantification can lead to a false sense of certainty. But understanding that your investment bets may or may not pay off means that you need to acknowledge the risks that you are taking, what the outcomes that you are looking for are, and whether to increase investment when opportunity arises, cut investment when it doesn’t, and how long you have before you need to make those decisions. As noted executive strategist Kenny Rogers so memorably opined: “Know when to hold ‘em and know when to fold ‘em”.