One thing I have noticed talking to old people is that the past was nearly always better. My late grandfather was born shortly before World War I and would never tire of telling me how much better things were in the past and how much worse things were in the present.

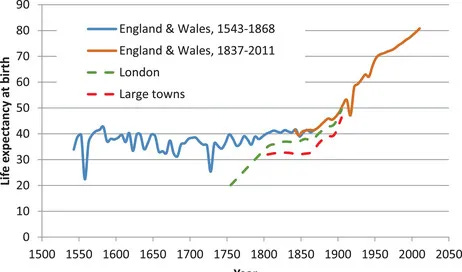

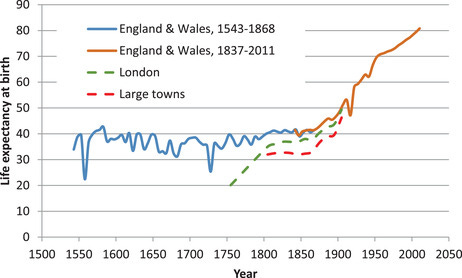

One thing that there was a lot more of in the past was death. If you live in a wealthy country, it is difficult to understand how common death used to be. In this article, Leigh Shaw-Taylor provides a detailed overview of living and dying in the UK over the last 500 years. For most of that time, average life expectancy was some time in your 30s. That meant that over half of everyone born in, say, 1600, would be dead by 1640. Death was everywhere and mortality was at John Wick combatant levels.

It started badly. Infant mortality was particularly high. The graph below is a “survivorship curve” - with death picking people off like a cheesy serial killer in a slasher movie. You had about a 30% chance of not making it adulthood and there was a steady line down with only a third of people making it to 60. And it was far worse in the cities - in 18th century London, deaths outnumbered birth. Without migrants from the countryside, the city would disappear.

What were the culprits? Famine - yes. War - yes. But particularly infectious diseases. In England and Wales in 1850, nearly half of all deaths were caused by infections. By 2012, it was 6%. This miracle can be seen in the chart. The average life expectancy is into the 80s and infant mortality is still tragic but very rare.

How was this achieved? Better nutrition (starving people are vulnerable to disease), sanitation, and then treatments such as inoculation for major killers like smallpox. The development of antibiotics during World War II took things to the next level. The benefits of modernity have not been evenly shared but as Shaw-Taylor notes, even the modern country with the lowest life expectancy (the Central African Republic) still has a longer lived population than England in 1900.

And we achieved all this despite ignorance. Viruses are too small to be seen via a regular microscope, they need the kinds of electron microscopes that weren’t invented until the 1930s.

When it comes to mental health we are even more ignorant. We have bunches of symptoms that we label as diseases. To get a major depressive diagnosis, you need to exhibit greater than five of nine symptoms such as depressed mood, fatigue or insomnia in a two week period.

About 5% of people globally suffer from depression but we do not know what causes it or why. We suspect that unipolar depression is different to bipolar depression (certainly it seems to respond differently to certain medications). We think that neurotransmitters like serotonin are implicated but we don’t really know how. We see a mix of genetic and environmental (both physical and psychological) factors causing episodes. But we don’t know which treatments will work. We live in a world of guesses. Our knowledge of mental health issues is equivalent to our 18th century knowledge of physical disease. We doubtless both under and over diagnose - and we really have no idea how much we do of either.

Our ignorance does not prevent us from making progress, just as we made progress with physical ailments despite a deep ignorance of the processes that underpinned them for most of our history.

For me, this source of both optimism and humility. As a species, we have reduced our physical suffering in a relatively short period of time. That is a tremendous achievement (that we should not squander in fits of paranoia or greed). And we still have much to find out about our natures.

The past can never kill you. Only the future can. So as you get toward that end, the apocalypse of your death is always closer and the past continues to get far away enough to be remembered fondly. Lots of psychology going on!

https://www.polymathicbeing.com/p/apocalypse-always

Worth thinking about healthspan as well as lifespan changes - sometimes the end of life years are very low quality, which is reducible with some significant pre-planning.