We Mean It Man - No Future Part 5

Who Cares?

Previously I talked about my experience with the Futures industry, some participants in that industry, some thoughts in Science Fiction, and the practices of History.

Noted Futurist and author Nikolas Badminton recently said: “The years of promotion that futures thinking and foresight can supercharge your strategic thinking has worked.”

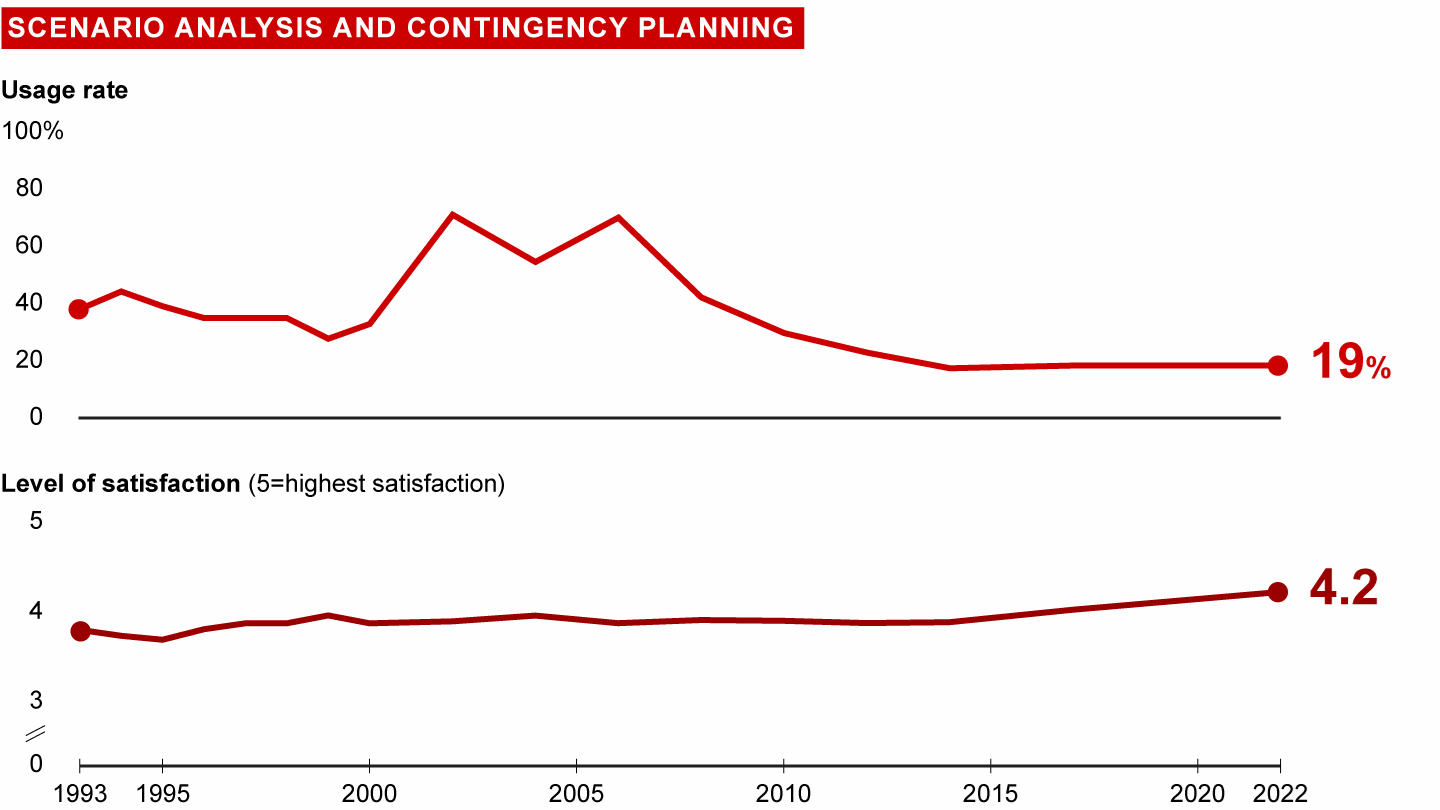

He goes on to say a lot more that I will come to presently. But first I want to examine this first claim. And I want to start with this chart from the Bain Management Tools Survey. The survey is like a Top Of The Tops for management fads trends. It’s sample size is over 1000 execs and it’s the closest thing to a trendometer for MBAs.

What’s obvious here is that since the end of the Cold War, the glory days for scenario analysis was the 00s. Interest in scenario analysis shows a significant drop-off post-2008 global financial crisis (GFC).

This contraction in interest is not just limited to foresight approaches. The Bain team note: “Managers appear to be increasingly sophisticated in their use of tools, jumping on fewer fads and carefully selecting the tools they use. Back when we first launched this survey, tools had much higher usage rates than they do today” But truly popular tools like Digital Transformation have 46% usage rate. On the flip side, satisfaction rates for foresight appear to have risen slightly.

So the data we have seems to indicate that the use of foresight tools by businesses has declined over the last 15 years. So I asked NB for the data behind his claim and he directed me to this paper: Corporate foresight and its impact on firm performance: A longitudinal analysis. It’s a very interesting piece of research that I want to carefully pick apart. It has a number of components:

There’s a survey that aims to test two things:

The need for corporate foresight (e.g. “How well can the speed of technological change be estimated in your industry sector?”)

The maturity of the corporate foresight function (e.g. “We are scanning the technological environment.”)

That survey is then used to identify whether a company’s maturity is aligned to its need.

The survey was answered by 89 companies in 2008.

The financial performance (EBITDA) of the companies was measured in 2015.

Various statistical tests were then undertaken.

Here is a good point to state my position: I think that foresight when done well can contribute to the formulation and execution of effective corporate strategies. There. I said it. Now let me tell you the things and I like about this research and the things that I don’t.

Things I like:

The attempt to define both need and maturity. The framework here is thoughtful.

The attempt to map it to performance and some of the statistical tests used.

The longitudinal approach.

Things I don’t like:

Survey instruments are very crude - especially when you are asking people to make detailed judgments about what goes on in their organizations. Asking people what ERP system they have and whether they like it or not: fine. But based on 20 years working in knowledge management, let me tell you that managers are terrible at accurately answering questions like: “In our company, information is shared freely across functions and hierarchical levels.” They either don’t know or have a massively distorted view of the facts on the ground.

The title. The study does not show the “impact” of corporate foresight on company performance. It just shows a correlation between the two. There is some effort to control for industry profitability but organizations use many tools (as we see from Bain). How do the authors know that some other tool accounts for the differences in performance? I suspect that foresight does have an impact on performance but this study does not prove it.

The sample size. Of the 467 firms invited, performance data was only available for 70 - or 15%. This sample likely has a bias towards an interest in the topic in the first place.

One final thing to note is that the original survey was in 2008 - which the Bain data tells us was the peak of of corporate interest in foresight. How many of the respondents to the 2008 survey were still in their roles when the 2015 performance data was collected?

Back to Badminton’s article. He basically says that now everyone is doing futures work, care must be taken that the work is of sufficient quality not to damage the organizations procuring it or the broader reputation of the field. I think such concerns are valid - yes, Jacob, I am going to mention Shingy here.

However I want to suggest that rather than just being an issue of supply (untrained wannabe futurists), it is mostly a problem of demand. As we have seen, the average CEO is in the role for less than 5 years and any part of their bonus that goes out more than 12 months is considered “long term”. Corporate longevity is declining.

I don’t want to say there is no market for serious futures work nor does everyone lack to will and skill to apply it. But these are the minority.

Shingy is who he is because there is a market for his schtick. The punters do not want thoughtful, considered explorations of possible futures. They want some stuff about AI they can put in the “Innovation” section of the Annual Report.

Here we are now, entertain us.

Nice article, Matt. As a sometime practitioner and fan of scenario planning, the research you cite strikes a chord with me. On the one hand, I still believe the approach has merit and efficacy when correctly applied to the appropriate question or industry. OTOH, I think that in this case it seems to be conflated with futurist thinking and predictions, which are in fact not the same thing.

I believe where long-cycle, big bet decisions are a central part of the reality of a given business or industry, scenario planning still has a very important role to play and can be of enormous value. It is not, however, that applicable in very many areas; and so perhaps it is not accurately represented in the research you were looking at. Or?

Arizona State University has an Applied Futures Lab that I've worked with in the past which is very useful. They do Futurecasting (defining what you want to achieve) and Threatcasting (defining what you want to avoid) The hardest part is quantifying the impact but that typically should just fall into general Risk and Opportunity managment vs. anything special.

What I like best is how it gets people to open up and be more imaginative about classing R&O in ways that allow the organiztion to unlock innovation.