The Three Mandates

Vote for an electrician

Manning Clifford writes about the “Staffer State”.

“I think that, for better or worse, the most compelling answer is that Australia is a staffer state. That is: the top set of decision makers in our society spent their formative years as political staffers, rather than in other roles. The impacts of this are non-trivial and worthy of reflection.”

This is about many things but, in particular, it is about the professionalization of politics and the narrowing of political parties. It is something that I have been concerned about since at least 2010 and it is not good. Let me explain why.

Being a politician in a modern democracy is not like most other jobs. In most jobs, you have a set of skills that enable outcomes that people will pay you for - be it building walls or doing accounts or running a shop. There may be formal training. And if there is not, then there is certainly an expectation that experience in what you are doing is good. That’s the whole point of having a CV. If want to be an airline pilot, you won’t get very far if you have done no training and you have no experience. Or at least I hope you won’t. And modern governments are full of professionals whose job it is to have expertise in how certain things get done - e.g. taxes collected, wars fought, confusing road signs placed.

Politicians are different. In a representative democracy, their role is to represent their constituents. They need to understand their constituents and be capable of representing their wishes through the political process - as confused and contradictory as those wishes might be. They don’t need to be experts in any knowledge domain except the wishes of their constituents.

I would suggest that the legitimacy of representative comes from three mandates.

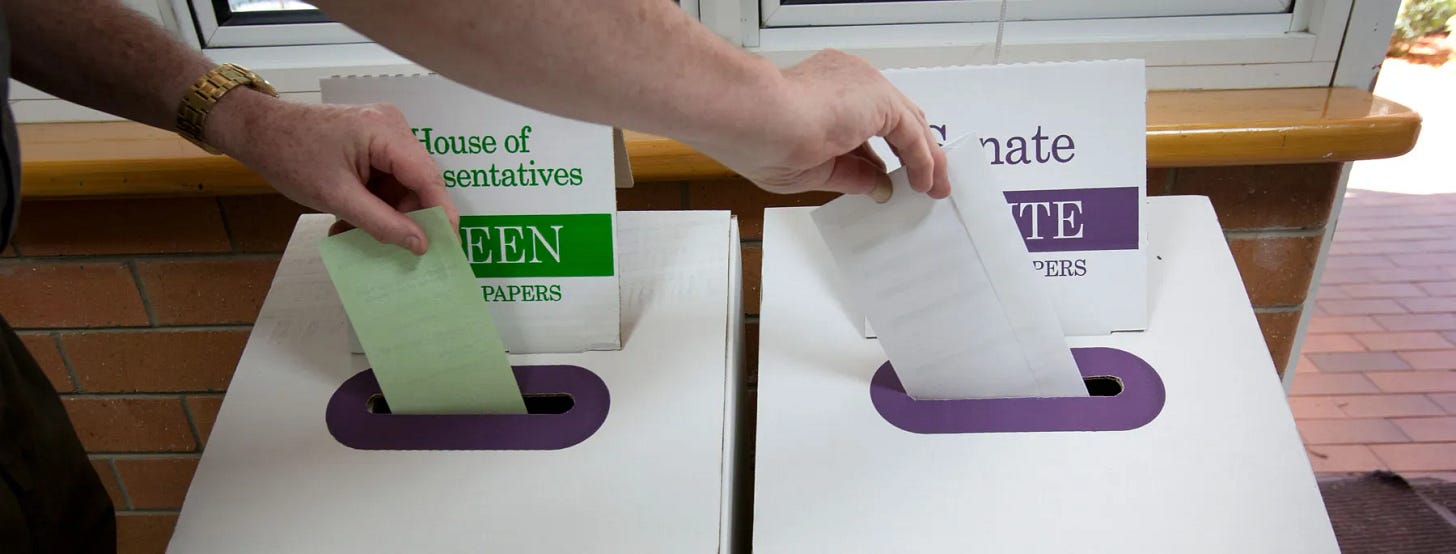

The mandate of the ballot. You win the election according to whatever rules are set - e.g. first past the post, preferential voting, lotto, who has the bushiest eyebrows, etc. This is the most obvious mandate and sometimes people think that it is the only one. But I think two other manadates need to be considered.

The mandate of the party. Human beings are social animals and naturally form tribes and coalitions. It’s just what we do. So while older representative bodies (Parliament, Congress) were originally established without political parties, they always tend to form over time. As much as people might despise them, parties are inevitable. Being part of a party provides a representative with legitimacy with the supporters of that party. Now a problem emerges when parties no longer represent meaningful coalitions to the majority of voters. In some countries and times, mass membership of political parties prevents them from drifting too far away from their electorates. But in many countries, political party membership has dwindled, leaving them vulnerable to takeovers by niche interest groups. The mandate of the party is not what it was.

The mandate of the self. Fundamentally, voters must trust the politician they vote for. They have to like and respect them. They have to think that the politician likes them. They have to see something of themselves in the politician. And it is here were the professionalization of politics causes harm. Nearly all politicians in the UK and Australia have degrees but less than half of the electorates of these countries do. Politicians in democracies typically have studied Law, Economics, or Politics. Very few have backgrounds in Engineering or Medicine. Even fewer are electricians or plumbers. It wasn’t always this way. The union movement provided a route for ambitious and able working class people to gain political office but now that has largely been replaced by university-educated political staffers. The mirror the representative holds to the electorate is broken.

A couple of weeks ago, I was at the Wheelwright Lecture on “Should we abolish universities?” (my answer: I don’t think we’ll need to). In conversation with some other attendees, I made exactly the point: Why don’t we have more electricians in parliament? Someone made the counter point that we should want our politicians to be well-educated. To which I would say, there are many ways of gaining education and experience and a degree is only one of them. Just because someone has been to university does not mean that they have learnt anything.

Concerns about diversity among our elected representatives tend to focus on obvious identity markers like gender, ethnicity, and sexuality. However we also need to be aware of background or to put it in a way some of you might prefer, their character and ethos as developed and demonstrated through their life experience.

We need politicians with as diverse characters as the electorates they represent.

This seems to reflect the broader economic trend of the professionalisation of most work, not just politics? We once had more trades people in parliament. Some even became prime minister! I don’t think a young Ben Chifley becomes a train driver anymore, he gets a uni education thanks to HECS and works as a union or Labor staffer.

Is it possible that Byrne Hobart's theory that we are identifying and "streaming" talent much earlier and this might partly explain why we no longer see plumbers in parliament? In the 50s you could be born extremely smart but poor, have no chance of going to uni so take a trade. Being extremely smart you may be able to do any number of jobs and so could "work your way up from the mail room" as it were. These days if you're smart and conscientious, you are much more likely to get a high ATAR, perhaps a scholarship and end up at uni even if you grew up very poor (an accountant friend of mine has done just this!) so we should in general now expect those people who were encouraged into trades to have fewer diamonds in the rough than we used to in the 50s. The diamonds were all found already!