Tempo - Part 1: The Fast Transients of Hüsker Dü and John Boyd

“Too much speed is like too much light... we find it blinding” – Paul Virilio & Sylvère Lotringer

Sometimes a cover is better than the original. The Byrds’ version of Eight Miles High is fine. The lush harmonies are offset only by the minor turbulence of Roger McGuinn’s efforts at a John Coltrane impression on his guitar.

If the original is a pristine DC-9 levitating off the ground into the California blue heavens and bright sunshine then Hüsker Dü’s 1984 cover is a rust-scabbed F-16 hurling itself into combat in a storm-roiled Minnesota sky. Grant Hart’s supple drumming is an elephant pirouetting. Bob Mould’s primal yelling and noisenik guitar are the oncoming storm. Greg Norton just does his goddam job – which is both providing bass and providing a base - gently anchoring his brilliant yet unstable bandmates.

Husker Du’s love of sheer velocity (and illegal stimulants) was signalled by the title of their first album: “Land Speed Record”. The cover of that album featured the stars-n-stripes drapped coffins of dead US war veterans. I find it completely unlistenable, an Umlautish mess.

The Eight Miles High cover was a pivot point in their musical development. Combining melody with raw noise, they pointed a way out of the hardcore punk dead end of always crashing in the same car, only slightly faster each time. Hüsker Dü’s love of 60s pop and tortured equipment would later bloom into the steel roses and hardcore psychedelia of “Warehouse: Songs & Stories”. While never troubling the charts in the 80s, their sound was a direct influence on such minor-league no-marks as The Pixies, Nirvana and Radiohead.

Meanwhile, John Boyd was… difficult:

“so profoundly insecure that he stalked food courts to hunt down and physically assault people whom he perceived had not shown him proper respect”

“defeating his students using an oft-repeated manoeuvre”

“later admitted to copying the charts after denying it for years”

“it was a fourteen-hour briefing split into two days. Boyd refused to shorten his briefings or to distribute summaries or slides to those who did not attend, insisting on being given the full amount of time, or nothing.”

He had been a pilot in the Korean War then a flight instructor at the USAF Fighter Weapons School and finally, post-retirement, a Pentagon analyst focused on first fighter design and then everything. He never published a book – only a few brief articles and 327-slide magnum opus that would form the basis of his 14-hour lectures. What remains of his work is by turns brilliant, bracing, bumptious and bathetic. I don’t know why Darwin, Godel, Heisenberg and Clausewitz are wedged together on a slide (perhaps as a guest list for the world’s most awkward dinner party) but there they are. And writers in glass houses should not throw stones at the magpie intellectualism of others. Today he would doubtless have started a blog in 2006 and now be hosting a YouTube channel – perhaps challenging Jordan Peterson for the “disaffected young man” demographic. Or he might have risen to become the Chief of Staff to a populist Prime Minister.

Boyd makes some acute observations about the nature of war – he is especially critical about a narrowly technical view of military might – i.e. superiority goes to him with the biggest tanks and bombs. He sees war as having physical, mental and moral dimensions that wily politicians and generals must pursue in tandem to achieve victory. The states that are most “Boydian” today are Russia and North Korea.

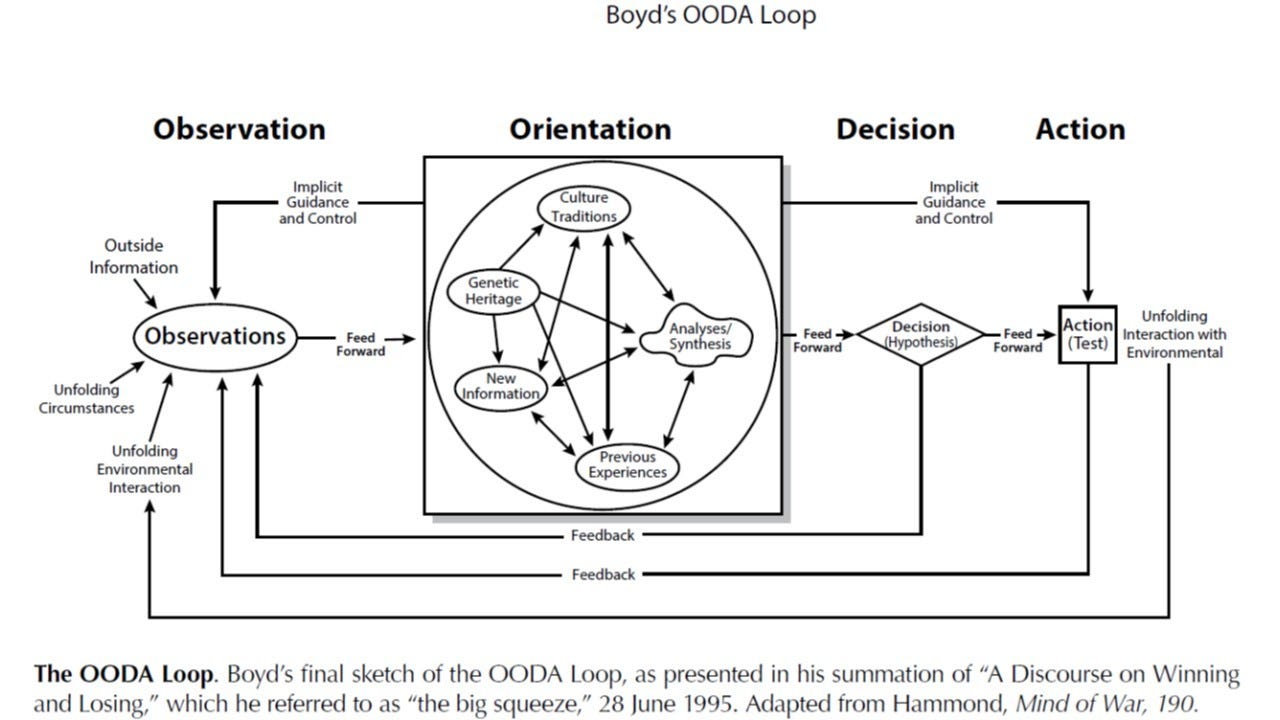

The thing that Boyd is famous for is the OODA loop. Lets break it down.

Observation. The skill of “noticing stuff” should be easy. It’s not. Noticing stuff is really hard. Most of the time we are encouraged not to notice things but to go on with our lives. Noticing stuff takes effort and there are things that we would rather be doing with our attention. Some people make career out of noticing things – entrepreneurs, comedians, market and UX researchers, columnists. But they’re all a bit weird, obviously. People that notice stuff are. But in combat, noticing stuff can be a matter of life and death. People that fail to notice stuff don’t get called “easy-going” nor do they get a promotion for being “a reliable teamplayer” – they die.

Orientation. As good as noticing stuff is, it’s not enough. You need to process what’s coming in. There is no one way of doing this. There is no right way of doing this. However there are a bunch of wrong ways.

Sticking to one grand theory of everything (i.e. being a Tetlock hedgehog).

Relying on a narrow set of precious experiences (failing to develop your Klein intuition).

Not engaging the full extent of your brain (Kahneman’s Systems 1 & 2).

In many situations, orientation can be a collective endeavour, where you use diverse viewpoints to raise your collective intelligence.

Decision. All the thinking and talking in the world won’t save your life if you don’t decide what you are doing to do. In some scenarios, where you have time and space and the stakes of getting it wrong are high, then a lengthy, consultative decision-making process is appropriate – e.g. agreeing new planning standards for a city. In others, a mediocre decision now is far more effective than a brilliant decision later – e.g. when you are engaged in a dog fight. The trick is to know what scenario are you in. You may walk into what you think is a planning meeting and it suddenly turns into a dog fight.

Action. The word beneath in parentheses deserves some attention. Test. For Boyd, actions are both definitive and preliminary. You need to act. Without action, there is nothing, only death. But no action ever stands by itself, it feeds back into the OODA loop through “Unfolding interaction with the environment”. It is iterative and dialectical. Those of you from a software development background will recognise that an OODA loop looks very much like an agile sprint.

There are two final thought that I want to leave you with: tempo and competition

Tempo: A simplistic reading of the OODA loop is that you just need to do it quicker than your opponent to win. As Frans Osinga elaborates, there are more advantages in changing tempo than simply going faster. The key is adaptability not velocity. Perhaps introducing some 60s pop into your land speed record hardcore.

Competition: The OODA arose out of the experiences of one man engaged in aerial combat. Dog fights are the modern martial form closest to the staged combat of the ancients (David and Goliath, Achilles and Hector). However not everything in life is a battle between two opponents. Perhaps another phrase for “getting inside your opponent’s OODA” is “understanding them”. Or even “falling in love”.

With her grandmother's face and her father's brown eyes

Her own force of will to her mother's surprise

A whole look about her that says that she may

She lifted her arms and she floated away

OODAs are useless if the decsions reached aren't optimal for the situation. More bad decisions than your opponent's fewer good ones will still lead to your defeat. Ready, fire, aim is generally not the way to win a dogfight.