Ignorance Management - Part 2: Error

To err is human

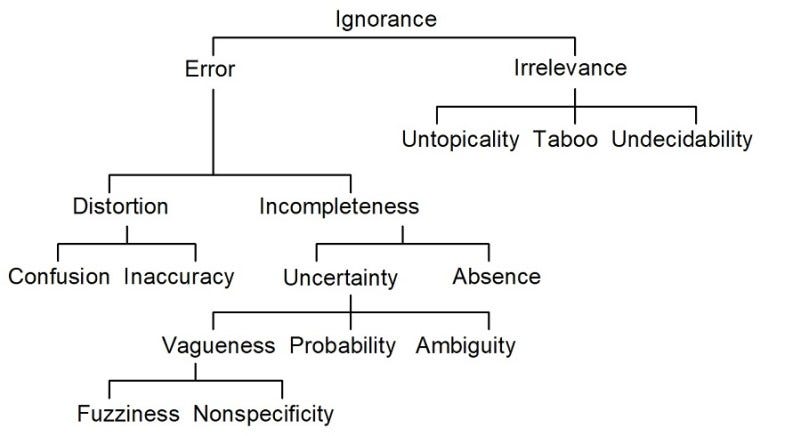

Continuing with Michael Smithson’s taxonomy of ignorance.

Confusion is mistaking something for something else. Some organizations deliberately cultivate confusion - in a practice called Agnotology - e.g. tobacco companies manufacturing doubt about the causes of lung cancer or fossil fuel companies doing the same for climate change. It’s not only a business tactic. Organizations often unwittingly confuse things. They are used to seeing the world in a certain way and everything gets slotted into the frameworks that they use. The classic example is a company seeing another company as not a competitor because they do not offer the same service but may replace it in some new way (e.g. newspapers and Google).

Inaccuracy amounts to mis-estimating something. As we have recently seen, most organizations are mediocre at estimating things. And as Flyvbjerg says, these mis-estimations are both political and behavioural (and conscious and unconscious) in cause. In my experience, organizations get quite good at estimating what they need to do frequently. However infrequent activities can be very expensive if you get them wrong.

Absence is missing information. The world is full of missing information. A key question is: “why is the information missing?” It may be that it is:

Impossible to find e.g. what happens inside a Singularity, a voice recording of Homer.

Highly unlikely to ever be found e.g. a drafting copy of a Gospel.

Expensive and/or time-consuming to find e.g. what every single person in the world thinks about milkshakes.

Easy to find but unimportant so no one can be bothered e.g. what I think about milkshakes.

And where there is missing information there is opportunity. Steve Blank defines a startup as ““a temporary organization designed to search for a repeatable and scalable business model.” Or to put it another way, a startup should exist to leverage missing information.

Probability is uncertainty about whether something is true or whether an event will happen. Much of the world seems to be inherently probabilistic. There’s a problem with this. Human beings are not good at probabilistic thinking. Probabilistic thinking requires data and data is not something our forebears had much access to. Some groups (e.g. actuaries) cultivate probabilistic thinking but they are rare. In particular, senior executives often have more confidence in their guts than probability calculations - with predictable results.

Ambiguity refers to distinct possible states. The example that Smithson gives is “this food is hot” where the food may be either spicy or at a high temperature. Ambiguity is built into human communication because it is impossible in practice to state something completely unambiguously. If it was possible to eliminate ambiguity from language then the legal profession would not exist. There are always edge cases. Typically ambiguity trips people up in things like contracts and software programming. However ambiguity is also a tool to be deployed. Politicians use ambiguity to promise different things to different audiences without contradicting themselves. Humans are as big on ambiguity as they are small on probability.

Fuzzy vagueness refers to fine-graded distinctions and blurry boundaries and is specific. For Smithson, an example of this are the ways that colours shade into each other on a spectrum. It is difficult to say exactly when yellow becomes orange. This is something that is the result of living in a world continuous (rather than discrete) properties. However human beings can turn continuous things into discrete categories that have immense power (e.g. what putative “race” you are, whether you are mentally ill or not) - decisions that are at once arbitrary and far-reaching. The arbitrariness should make us humble but it rarely does.

Nonspecific Vagueness is simply as it says. Extra vague vagueness. “Sydney is far away”. Is that 3 kms or 3000 kms? Everyday speech has a lack of precision because most of the time we have the context to understand that the other speaker is saying. However in many work situations, we need more precision than every day speech allows. Hence the need to constantly ask what people mean by their statements. The biggest communication problems tend to occur when people are under the delusion that they are communicating in the same manner.

I think Smithson’s taxonomy could be broken down further. The taxonomy is not very balanced. Three terms go down three levels but two terms go down six levels. And some of my comments might indicate what those sub-levels are.

What the taxonomy does do is highlight the ways in which ignorance is managed or unmanaged in organizations and the opportunities to manage it better.

Next: Ignorance Jobs More Ignorance